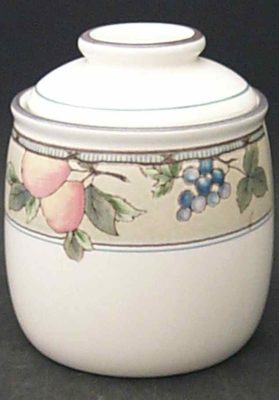

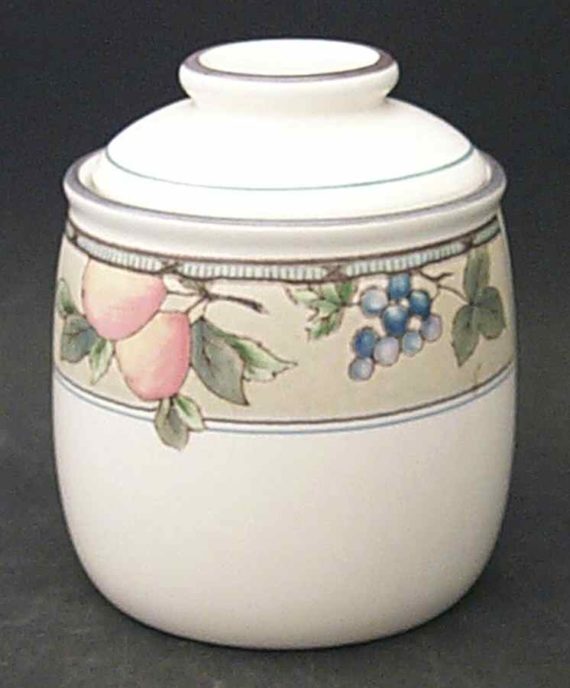

Description

Mikasa Garden Harvest Coffee Canister

No Seal

4 3/4 in

Colorful fruits and leaves by the bushel enliven the table with the tones of the orchard. This Mikasa stoneware is a longtime favorite for everyday use. It is dishwasher safe, oven safe, freezer safe and microwave safe. This pattern coordinates perfectly with casual stemware and flatware. As good as new.

AAA Resale will combine shipping on various dinnerware and other small items. Please call us at 843-347-3350 before placing your order for combined shipping price.

Mikasa Patterns

Company Perspectives:

Mikasa’s multiple brand strategy allows us to target our diversified product line to consumers through a number of distribution channels. Our four proprietary brands of Mikasa, Christopher Stuart, Studio Nova and Home Beautiful are marketed in North America through 152 Company-owned and operated stores and the Company’s retail account base of over 7,000 accounts. These retail accounts represent traditional and non-traditional channels of distribution and include major department stores in North America as well as catalog showrooms, corporate and incentive award accounts, home shopping television, hotels, mass, merchants, military base exchanges, restaurants and warehouse clubs.

Company History:

A fast-growing retailer and wholesaler, Mikasa, Inc. sells causal and formal dinnerware, displaying its greatest strength in the casual segment of the market (settings that retail for less than $130). Mikasa sold its dinnerware and decorative accessories through wholesale accounts in the United States and abroad and through a network of approximately 150 U.S.-based factory outlet stores. Unlike many of its competitors, the company did not own manufacturing facilities. Instead, Mikasa contracted out designs to approximately 175 factories in 25 countries. Production was concentrated in Germany and Austria, where 30 percent of the company’s merchandise was manufactured. The flexibility engendered by contracting out production enabled Mikasa to introduce numerous patterns into the market each year and quickly expand production of designs that proved popular. During the 1990s, the company increasingly broadened its product categories, experimenting with cookware, bath accessories, and other decorative accessories for the home–all patterned after its popular dinnerware designs. The company was partly controlled during the late 1990s by chairman emeritus George Aratani, the son of Mikasa’s founder.

Founded in the 1930s

Mikasa’s predecessor was a company named All Star Trading, founded in 1936. The ties that connected All Star Trading and Mikasa were familial–the business legacy of the Aratani family. Setsuo Aratani, a Japanese-American, started All Star Trading as an import-export enterprise specializing in trade with Japan. When hostilities between Aratani’s source country and his supply country erupted on December 7, 1941, the business abruptly closed, but following World War II, Setsuo’s son George and a partner named Alfred Funabashi revived the trading company. The younger Aratani and Funabashi sold flash-frozen tuna and developed the company into one of the largest importers of toys, distributing its merchandise through a half-dozen department store chains on the East Coast. Before the end of the 1950s, the pair began concentrating on importing china made in Japan, using the trademark they adopted in the 1950s–“Mikasa,” Japanese for “three umbrellas.”

The gradual move into the chinaware business evolved into the company’s exclusive occupation by the early 1960s. In 1965, the company’s path crossed with a young department store merchandiser named Alfred Blake, who was impressed by the Mikasa designs he saw while working with Hudson’s Bay stores in Canada. Blake’s interest was sufficient to prompt a career move. He joined Mikasa as a commissioned sales representative for western Canada in 1965, when the California-based company was collecting $5 million a year in sales. Blake’s esteem for Mikasa’s merchandise translated into high sales, fueling his promotion within the company’s sales ranks. When Alfred Funabashi died in 1976, the impressive Blake was named president and began working alongside George Aratani.

Expansion Begins in the 1970s

Under Blake’s operational control, Mikasa flowered into a vibrant enterprise. He made wholesale changes with alacrity. Blake broadened the company’s line of merchandise, adding crystal stemware and new, less expensive brands to buttress the company’s flagship Mikasa brand. For housewares departments in department stores, Blake created “Studio Nova,” which sold for roughly 40 percent less than Mikasa brand china. For mass merchants and discount stores, Blake created a more affordable brand, dubbed “Home Beautiful.” Blake’s innovative approach also broadened the awareness of the Mikasa name and its assorted brands. He opened a showroom in New York City, where the company’s tableware was showcased in mid-Manhattan, and in 1978 he directed the company’s foray into the retail sector, establishing an outlet store in a warehouse in Secaucus, New Jersey–the first of many more to follow. Blake’s influence on the maturation of Mikasa was profound, evidenced in the robust financial growth of the company during his first decade of control. When Blake was named to the presidential post, Mikasa was collecting $26 million a year in sales; by 1985, the company was generating $137 million in annual sales.

By the mid-1980s, confidence at the company’s headquarters was running high. Blake and a group of senior executives, who each held small investment stakes in the company, were ready to significantly increase their financial investment in the company. In 1985, the management group initiated a leveraged buyout (LBO) of the company, offering $1 million in cash and borrowing $31 million to obtain ownership from George Aratani. The LBO, completed in 1985, was a sign of the executives’ faith in Mikasa’s future, but to their chagrin, outside influences conspired against the new owners shortly after the deal was concluded.

Mid-1980s Crises Alters Strategy

In 1986, Japan’s currency began to appreciate quickly against the U.S. dollar, making goods produced in Japan more expensive in the United States. To make matters worse, U.S. department stores were struggling with their own ills, forcing some retailers to close stores and others either to consolidate or to streamline their operations. The net effect was fewer china departments within department stores nationwide, delivering a second pernicious blow to Mikasa’s business. After their first year of ownership, the new owners had little to celebrate: losses for the year amounted to a numbing $3.6 million. The future would have looked even bleaker had Mikasa’s group of executive-owners known the tableware industry was destined for a decade-long slump. Between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s, the “tabletop” industry, which included flatware, cups, saucers, plates, crystal, serving platters, and Christmas plates, recorded little growth.

Although the company did not escape the 1980s without experiencing several difficult years, strident growth arrived as the 1990s began, thanks in large part to the measures taken by Blake. His response to the growing strength of Japanese currency was crucial to the company’s trend-bucking success. Blake moved some of Mikasa’s production out of Japan to low-cost, contract operations in Malaysia, Thailand, and Yugoslavia, essentially doing what Nike did during the early 1980s to record prolific growth in a lackluster industry. While other chinamakers struggled to make money in the face of rising labor and operating costs incurred from their own factories, Mikasa thrived mainly because it owned no factories. The company contracted its designs to other manufacturers and prospered, while many of its competitors were held in check by escalating overhead.

The cost-savings realized from outsourcing production also gave Mikasa another important advantage, namely, flexibility. The company could quickly increase production volume on popular patterns and quickly abandon designs that failed to impress customers. Additionally, enhanced flexibility in production enabled Mikasa to churn out a greater diversity of patterns than many of its competitors. With a larger number of designs introduced into the market each year, the company’s odds for success increased, frequently putting Mikasa on the leading edge of emerging trends. Blake also began to emphasize the expansion of the company’s outlet stores, which reduced the reliance on department stores and strengthened Mikasa’s brand identity.

Blake’s meaningful operational changes began to pay substantial dividends by the beginning of the 1990s, as the company strove to shrug aside the industrywide malaise affecting its competitors and effectively market tableware to what Blake referred to as the “McDonald’s/microwave generation.” To accomplish this goal, the company moved in three general directions. The first relied on Mikasa’s production flexibility. When the company identified a popular design from one of its numerous pattern introductions in a given year, it would quickly orchestrate the production of the particular design on a number of supplementary products, such as servers, carafes, napkin rings, and butter dishes–occasionally branching far afield by adorning the popular pattern on non-tableware items such as picture frames. “Customers,” Blake remarked, “are treating dinnerware like sportswear, and accessorizing,” so the company followed suit and began broadening and diversifying its product lines and product categories. The other two areas of emphasis that fueled the company’s rise were international expansion and the expansion of its network of retail stores. In 1991, Mikasa formed a joint marketing venture named Mikasa Europe Distribution with a German partner to market the company’s products in Europe. As the 1990s progressed, Mikasa intensified its efforts overseas, adding a relatively small yet growing facet to its operations. A greater contributor than international sales to the company’s revenue growth during the 1990s was the company’s chain of factory outlet stores. As their numbers grew, providing a means to dispose of excess inventory, the retail stores became increasingly important to Mikasa’s well-being, accounting for roughly half of the company’s total sales by the early 1990s.

Between 1989 and 1993–years that encompassed a nationwide economic recession–Mikasa’s sales increased at a compound annual rate of 14.2 percent, from $175 million to $299 million, and its net income grew at a compound annual rate of 34.4 percent, swelling from $7.7 million to $25.2 million. By this point, Mikasa sold its cups, saucers, plates, crystal, and other dinnerware items through independent distributors in eight countries. The company owned its own buying agency in Japan, controlled its joint marketing venture in Germany, and operated retail outlets in more than half the country. Much had been achieved since the troubled months following the LBO, but more was yet to come. To fund expansion, the company filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in April 1994 for an initial public offering (IPO). Blake was hoping to raise $27 million for the expansion of the factory store network and for international expansion. The IPO was completed in June 1994, yielding an estimated $23.7 million in net proceeds, providing Blake with a bankroll to fund Mikasa’s expansion.

1994 Public Offering Spurs Expansion

At the time of the IPO, Mikasa operated 75 retail stores. The company planned to open between 20 and 25 new stores during the remaining six months of 1994, and another 50 stores in 1995 and 1996. The stores, which averaged 7,500 square feet, generated nearly half of Mikasa’s sales, with the balance derived from 8,000 wholesale accounts supplying approximately 40,000 locations in the United States. To further expose the company’s range of merchandise, Mikasa sold its products through mail-order catalogs, striving to tap into demand through a variety of marketing formats. “Families,” noted Blake, “aren’t instilled with a tradition of dining elegance and butlers scurrying around with silver trays.” It was the company’s objective to instill a need for tableware, but not necessarily tableware that evoked dining elegance. In the formal segment of the market–settings that retailed for more than $130–Mikasa ranked fifth in the nation, but in the casual segment the company ranked as the market leader, controlling 40 percent of the market. Mikasa’s strength in the casual segment and its ability to roll out a range of ancillary merchandise in support of a popular design dictated its business strategy. Instead of limiting itself to marketing fine tableware, the company pursued a much larger customer base. “We’re not just competing against other chinamakers,” explained the company’s president, Raymond Dingman, Jr., whose prominence at Mikasa increased during the 1990s, “We are competing for the decorating dollar.”

Over the course of the next three years, Mikasa nearly doubled the number of factory outlet stores it operated. By 1997, after recording $372.3 million in sales for the previous year, the company had 140 stores in 40 states and contracted the production of its products at 150 factories in 22 countries. To stimulate further growth, the company began using its stores in 1997 as a testing ground for expanding its product categories. A line of cookware and a line of bath accessories debuted in some of the stores, representing one aspect of Mikasa’s growth strategy for the late 1990s and the years to follow. Dingman explained the three-part strategy: “First, we’ll work closely by extending existing product lines. We’re also looking to expand existing product categories. We think we can grow through acquisitions,” he remarked, unveiling a new potential method for expansion. “We expect to be a consolidator, not a consolidatee.”

As the company pursed the objectives of its growth strategy, it completed work on the infrastructure to support future expansion. In discussions dating back to 1993, company executives had evaluated the distribution and service needs of Mikasa, attempting to determine what the company would need in the future. From these discussions, an ambitious project was born for a new distribution facility to improve the company’s existing capabilities, which relied on distribution centers in Secaucus, New Jersey, and Laguna Beach, California. Mikasa broke ground on the project in March 1996, when construction began in Charleston, South Carolina. When completed in October 1997, the $60 million facility typified a state-of-the-art distribution center. Inside were 60,000 square feet of office area, 270,000 square feet of warehousing space, and 263,000 square feet set aside for shipping and receiving. At the dedication ceremony for the building, South Carolina’s governor was in attendance, the state’s Secretary of Commerce, and Charleston’s mayor, personages testifying to the momentous nature of the event. “Merchandising and marketing is changing,” Blake remarked, referring to the company’s new complex. “This is the future of the company; the new face of the company.” The advantages gained in service and distribution efficiency from the Charleston facility were expected to be realized as the company entered the 21st century. Other potential developments included acquisitions and a new breed of retail stores patterned after a prototype named Mikasa Home Store, which sold merchandise without the sharp discounts offered at the factory outlet stores. With these avenues of growth on the horizon, Mikasa prepared for the future, holding sway as the dominant designer and marketer of casual dinnerware.